These are Christopher Lloyd’s top 20 paintings on public view in the UK outside London. The first 17 are in chronological order; then there is a countdown of his top three. They are taken from his wonderful book, In Search of a Masterpiece: An Art Lover’s Guide to Great Britain and Ireland (Thames & Hudson). The descriptions have been freely adapted (with apologies ) from the book.

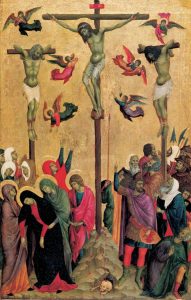

Duccio The Crucifixion c1320-15

Duccio The Crucifixion c1320-15

Manchester Art Gallery

This composition echoes that on the huge altarpiece, known as the Maestà, painted for Siena Cathedral. Unlike the Florentine school, Duccio favoured linear intensity and incandescent colour. The ethereal (flying angels) contrasts with the realistic (the blood-

spattered Roman soldier)

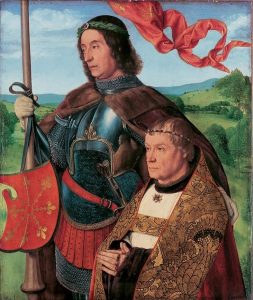

Master of Moulins Saint Maurice (or Victor) with a Donor c1480-1500

Master of Moulins Saint Maurice (or Victor) with a Donor c1480-1500

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow

A fragment from a lost altarpiece, possibly by Jean Hey. The detail is mesmerising: the warrior saint’s fur mantle, the donor’s cape; above all, the reflection of the donor’s profile in the side of the saint’s armour

Jacopo Tintoretto Christ washing the Disciples’ Feet c1547

Shipley Arts Gallery, Gateshead

Tintoretto, Tiian and Veronese were the great triumvirate of Venetian Renaissance painters. This is the original from San Marcuola in Venice (replaced by a copy, no-one knows why): an enormous canvas with vibrant brushwork and plunging perspective; the main business enacted in the lower corners. It once belonged to Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Tintoretto, Tiian and Veronese were the great triumvirate of Venetian Renaissance painters. This is the original from San Marcuola in Venice (replaced by a copy, no-one knows why): an enormous canvas with vibrant brushwork and plunging perspective; the main business enacted in the lower corners. It once belonged to Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Annibale Carraci The Butcher’s Shop c1583

Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford

Tremendous detail in a large painting of an everyday scene – but realism was common in Bologna, where this originated; it may even include portraits of the artist’s family. The painting came via the Dukes of Mantua, then Charles l’s collection, to hang in the

Tremendous detail in a large painting of an everyday scene – but realism was common in Bologna, where this originated; it may even include portraits of the artist’s family. The painting came via the Dukes of Mantua, then Charles l’s collection, to hang in the

college kitchen for many years. It was recognised in the 20 th century and moved into the gallery.

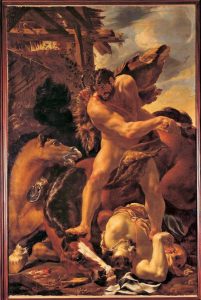

Charles le Brun Hercules and the Horses of Diomedes c1640

c1640

Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery

Hercules feeding Diomedes to his horses was somehow a tribute to Cardinal Richelieu and was an overmantel in his Palais Royale in Paris. The energetic composition of tangled figures is impressive

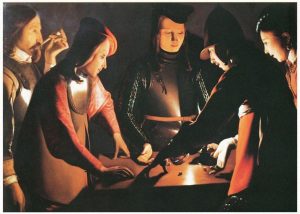

Georges de la Tour The Dice Players c1650

Preston Hall Museum, Stockton-on-Tees

Preston Hall Museum, Stockton-on-Tees

The painter was something of a mystery: little known of his life, a limited output, and enigmatic subjects. Here for example the man on the left is picking a pocket, and there may be some cheating. There is a striking use of light: the candle is even half-hidden.

Frans Hals Portrait of a Woman c1655-60

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

Second only to Rembrandt among Dutch painters, Hals’ portraits are confrontational and spirited. The angle of the shoulders, the tilt of the head, the smile – all convey movement and sparkle. There is a sophisticated handling of colour.

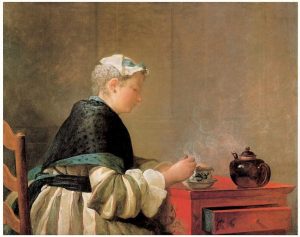

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin A Lady taking Tea 1735

Hunterian Arts Gallery, Glasgow

Hunterian Arts Gallery, Glasgow

Chardin was a quiet revolutionary in his choice of domestic subjects, in this case his wife. Although there are unresolved problems with perspective, the ruminative detachment is enhanced by soft colouring and emphasis on the materials

Joseph Wright of Derby A Philosopher lecturing on the Orrery c1764-66

Derby Museum and Arts Gallery

A document of the Enlightenment. Wright attended lectures like this, where an orrery demonstrates the workings of the solar system. The illuminating light (tenebrism) represents knowledge and symbolises the driving out of ignorance; on the faces of the

A document of the Enlightenment. Wright attended lectures like this, where an orrery demonstrates the workings of the solar system. The illuminating light (tenebrism) represents knowledge and symbolises the driving out of ignorance; on the faces of the

children it represents innocence.

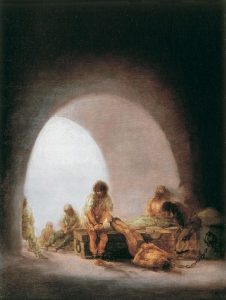

Francisco Goya Interior of a Prison 1810-12

Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle

Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle

Goya, now deaf and withdrawn, witnessed the Spanish insurgency against Napoleon; this small, gloomy picture was a result. The careful composition is strong; the misery of the wretched prisoners heightened by the arch and thick walls, hinting at other captives

beyond.

Johan Christian Dahl Mother and Child by the Sea 1840

Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham

Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham

Moonlight is a recurring theme in Romanticism, often used symbolically. Here it is partially obscured by cloud. Are the mother and child simply waiting to welcome the father home, or is the boat a symbol for the transience of life?

Ford Madox Brown An English Autumn Afternoon 1852-85

Birmingham Museum and Arts Gallery

Birmingham Museum and Arts Gallery

Although not a member of the Brotherhood, and interested in literary and social subjects, Brown was closely allied to the Pre-Raphaelites. John Ruskin did not like the mundane detail in this painting, but the view is spectacular and the dovecot suggests

the pair are lovers.

Sir John Everett Millais The Black Brunswicker 1859-60

Lady Lever Arts Gallery, Port Sunlight

An historical painting with telling references: Napoleon crossing the Alps in the painting on the wall, the anxious dog, the German soldier keen to get off to war (but ominously wearing black), his hand on the door contrasting with the worried, hurried embrace.

The model for the young woman holding on to the door handle is Charles Dickens’ daughter Kate.

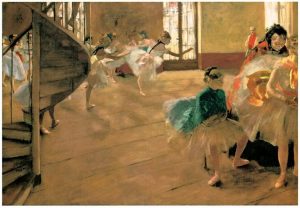

Edgar Degas The Rehearsal 1874

The Burrell Collection, Glasgow

Degas saw ballet as a metaphor for his own art: a physical challenge, the endless search for perfection – thus his frequent focus on rehearsal not performance. His composition is radical: the staircase makes little sense at first, figures are cropped, the view is into

Degas saw ballet as a metaphor for his own art: a physical challenge, the endless search for perfection – thus his frequent focus on rehearsal not performance. His composition is radical: the staircase makes little sense at first, figures are cropped, the view is into

the light (contre-jour) and there’s a void in the middle of the painting.

Franz Marc Red Woman (Girl with Black Hair) 1912

New Walk Museum and Arts Gallery, Leicester

New Walk Museum and Arts Gallery, Leicester

A rarity in Britain and possibly most important work by a German expressionist artist in a public collection. He was one of the Blue Rider group, who found inspiration in the medieval. The woman here is Eve in the Garden of Eden, her figure blending perfectly

with the surrounding. Inncocence lost?

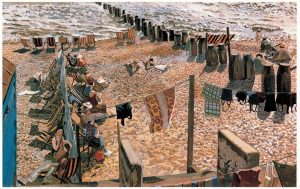

Stanley Spencer Southwold 1937

Aberdeen Arts Gallery

A significant year for Spencer: he was divorcing his first wife Hilda Carline (they were married at Wangford) and marrying his muse Patricia Preece (who continued to live mainly with her lover, Dorothy Hepworth, whose paintings she passed off as her own). Here the breakwater and beach hut anchor the composition , but the focus is on the mulititude of everyday objects that dominate the picture.

A significant year for Spencer: he was divorcing his first wife Hilda Carline (they were married at Wangford) and marrying his muse Patricia Preece (who continued to live mainly with her lover, Dorothy Hepworth, whose paintings she passed off as her own). Here the breakwater and beach hut anchor the composition , but the focus is on the mulititude of everyday objects that dominate the picture.

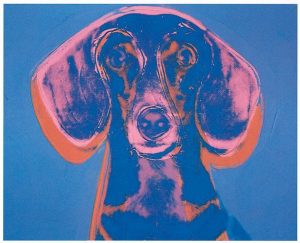

Andy Warhol Maurice 1976

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

The dachshund belonged to Gabrielle Keiller the Dundee marmalade heiress, and a major benefactor of this gallery. The medium is a polaroid photograph and a silk screen print heightened with oil paint – a mix characteristic of Warhol’s revolutionary approach to art. His subjects, too, were a mix of the mundane, portraits and historical events.

The dachshund belonged to Gabrielle Keiller the Dundee marmalade heiress, and a major benefactor of this gallery. The medium is a polaroid photograph and a silk screen print heightened with oil paint – a mix characteristic of Warhol’s revolutionary approach to art. His subjects, too, were a mix of the mundane, portraits and historical events.

The Top Three

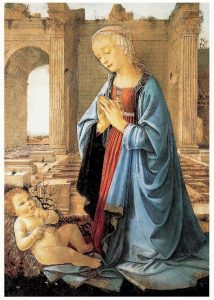

3. Workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio Virgin and Child c1468-70

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

A picture made for private devotion; its beauty lies in the simplicity of its pyramidal design. The child is routine, but the Virgin is unsurpassed. The Roman Forum background symbolises the passing of the old laws in favour of Christ’s. The damage the painting has sustained does not detract from the sense of quality – indeed of awe.

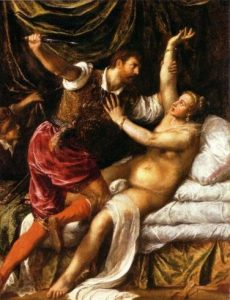

2.  Titian Tarquin and Lucretia 1569-71

Titian Tarquin and Lucretia 1569-71

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Most Renaissance artists have the chaste Lucretia killing herself, having been raped and forced by King Tarquin to admit adultery. This version is both more violent and laboriously detailed. The contrast in colours between the interlocking pair, the scissors-like movement of the flailing arms, the knife, the fear in her eyes – all bring dynamic propulsion.

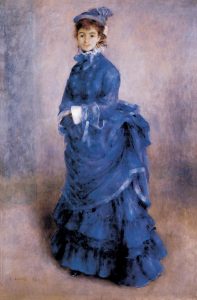

1. Auguste Renoir La Parisienne 1874

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

The finest full-length portrait in the whole of Impressionism, yet it represents a type rather than an individual. As always with Renoir, things are in flux: feathery brushwork, thin paint; and the rhythmic movement in the angle of the shoulders, the turn of the

head, the glimmer of polished shoe. She will pass us by, perhaps a greeting if we are lucky. Do we remember her? Are we dreaming? Such is art and such is the power of a masterpiece.