DOGGERLAND

We don’t claim to have invented Doggerland, but certainly W&BA was an early explorer of its often mythic significance – and the exploration continues.

At the beginning of 2015 Jan Dungey (who

invented Waveney & Blyth Arts) suggested we take a multi-disciplinary look at the landmass that in Mesolithic times connected us with mainland Europe. Nicky Stainton, Melinda Appleby and others took up the challenge and that April a number of what we like to call creatives gathered at Covehithe. Under the tutelage of a geomorphologist with specialist knowledge of Doggerland, various themes were discussed.

The idea was to assemble very broadly-based responses to the changes that resulted from the floods that depopulated what was a rich hunting, fowling and fishing ground. A film by Debra Hyatt gives an insight into those creative processes, watch here.

From that emerged a series of public workshops in the summer. The creatives had already been working on ideas inspired by Doggerland. They were then able to use the workshops to get the attendees producing performances, artworks etc. Poetry, song, photography, film, sculpture and painting were among the disciplines involved.

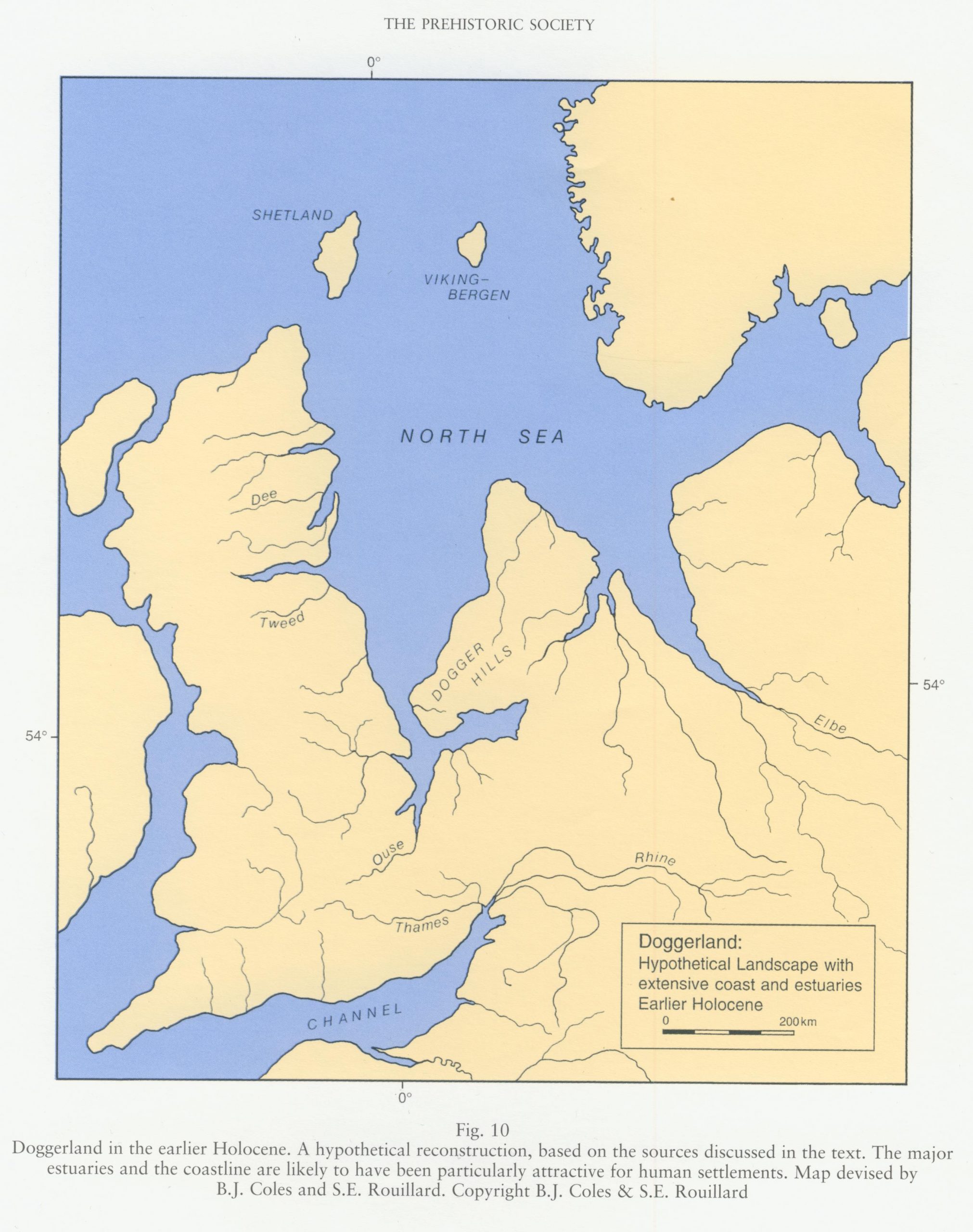

Then in November all this preparation and work came together for Discover Doggerland – a day at The Cut in Halesworth. Two academic presentations kicked it off. Professor Vincent Gaffney, a landscape archaeologist from Bradford University, brought news of his research into Doggerland. Using seismics, he and his colleagues have mapped huge areas of the early Mesolithic landscape off our coast. The work continues, including digging out sedimentary DNA. He was able to enlighten the big, enthralled audience about the past, present and future of what has become a rich research site. Googling him now demonstrates this.

Then in November all this preparation and work came together for Discover Doggerland – a day at The Cut in Halesworth. Two academic presentations kicked it off. Professor Vincent Gaffney, a landscape archaeologist from Bradford University, brought news of his research into Doggerland. Using seismics, he and his colleagues have mapped huge areas of the early Mesolithic landscape off our coast. The work continues, including digging out sedimentary DNA. He was able to enlighten the big, enthralled audience about the past, present and future of what has become a rich research site. Googling him now demonstrates this.

Nearer to home, Tim Holt-Wilson, a local geo-conservation activist, focused on the environmental story of Doggerland and the time dimension of coastal change. This extract from his blog (Mythic geography) gives a flavour of what he had to say:

No Mesolithic folk tales have survived about the drowning of Doggerland. Many people are likely to have been killed by the tsunami from the Storegga slide which swept over the land about 8,100 years ago. Over the generations, people would have watched their ancestral hunting grounds and sacred places being invaded by water; they would have become separated by widening tidal channels. Evidence for their camp sites, flint and bone tools now lies under the sea. Birds migrating to Britain would have found the task more challenging with each passing year. Driven by an enduring geographical instinct, we see them today clinging to the desks and masts of seagoing ships and offshore rigs, rather than to the twigs and branches of old Doggerland.

These two introductory speakers were then joined in a panel by Bill Jenman of Touching the Tide, a conservation project which helped fund our Doggerland project.

The rest of the day was devoted to enjoying the fruits of the many weeks of creative work in the various disciplines. Each practitioner’s work was inspired in some way

by Doggerland.

Film-maker Debra Hyatt showed both the film referenced above here and one based on a story by Melinda Appleby, Dreaming Doggerland.

Choir leader and singer Sian Croose grew up on the Norfolk coast, so was readily inspired by the Doggerland coast. As a director of The Voice Project she commissions new work from contemporary composers and creates large-scale site specific works for massed voices

Jeremy Webb specialises in landscape and coastal photography, so his shots of the fringes of Doggerland were very telling. He recently completed a project to photograph the Norfolk coastline – a documentary series which culminated in an exhibition and book, Spindrift. He is also interested in techniques such as pinhole photography and camera obscura

Maggie Campbell’s is a maker, sculptor and workshop leader who has worked with outfits like Footsbarn Theatre as well as in school and community settings. Her works frequently reference fossils and spiral shell-like shapes.

Paul Osborn’s ceramics reflect his interest in history and myth; he experiments with different techniques to produce unpredictable work.

Visual artist Jayne Ivimey gave a personal account of how she arrived at Doggerland and showed paintings which used materials collected locally to explore coastal erosion and landscape character.

Samia Malik’s songs are about language and belonging, and she is interested in themes of migration, change, recent and ancient history.

Writer Steven Watts focuses on place and time, language and memory:

Like flying without touch

Water moves underfoot

Footprints that are not mine

Beyond Doggerland

Among the audience for this event was celebrated local author, Julia Blackburn. Inspired by the story, she started her own, unique investigation of Doggerland. This led to in the publication in 2019 of Time Song: Searching for Doggerland. And she came back to the Cut to talk about the book. Like her books on subjects as diverse as Billie Holiday, Napoleon and the Norfolk fisherman turned artist Thomas Craske (Threads, 2015), Time Song is an inspiring mix of the factual and the personal. Julia Blackburn includes fragments from her own life with a series of 18 ‘songs’ and stories about the places and the people she meets in her quest to get closer to an understanding of Doggerland.

With her for this W&BA event was the renowned anthropologist, film maker and writer Hugh Brody. They had collaborated on her book and now discussed Doggerland. He also presented a film about the Canadian Inuits, whose lives in the early 20th century relate to all hunter gatherers, from the Neanderthals to the Mesolithic people who inhabited Doggerland a mere 7,000 years ago.

Even more Doggerland

Later that same year a terrific, if terrifying novel appeared called simply Doggerland. It tells of a man and a boy more or less marooned on disintegrating North Sea oil platforms. Author Ben Smith references Vincent Gaffney at the end of his book, and soon after publication popped up on Radio 4’s Start the Week, in discussion with… Julia Blackburn. So, our circle was very roundly completed.